I hate the world and all within

Its full of shit and full of sin

All I want to do is fly

There’s no room in my life to cry.

I hate the world and all around

Everyone wears a tear and frown

They smile at you, but they don’t care

You’re different, so they watch in fear.

I love to look at the setting sun

After a hard day of having fun

You sit back and watch light go

See darkness come with its own special glow.

I love the world of loving dreams

Where nothing is as bad as it seems

When things don’t seem to be going your way

Simply open your eyes and awake you stay.

All in all, its pretty fuked

Some things you like and some have you shocked

What can u do but go with the flow.

Till your time is up, u learn whilst you grow.

P.S. some drugs won't take no for an answer...

Sunday 30 September 2007

The Happy Medium

From the earliest known presence of mankind in the plains of Ethiopia through the emergent civilisations of Africa, Eurasia and the Western Hemisphere, to this day, in fact, mankind has struggled to strike a balance between what is needed for survival and what would contribute to legacy. One has only to consider the diverse articulations of the Upanishads or Buddha with that of Machiavelli or Protagoras to appreciate the breadth of the spectrum of perception.

This quest for balance led to the emergence of value systems – ethical codes or guidelines for daily life – some of which we recognise as religions.

Whether we believe they were revealed through divine intervention, as is upheld in Islam and Catholicism, or rather championed by visionaries or opportunists, as is maintained in more secular schools of thought, the fact remains these systems emerged at different times and in different civilisations around the globe.

All the while, indeed, sometimes seemingly in parallel, mankind has marched on, dreaming of perfection and the evolution of superman, as was considered by Dewey, Shaw and Nietzsche. Some see the development process as linear progression, while others advocate cyclic tendencies and act accordingly.

And yet here we are today – a diverse and yet dominant species who (as identified by Sayed Ashraf) have been able to mirror the characteristics of our Creator in our understanding of ourselves, our interaction with our fellow man and even the physical environment.

Yet still, the deeper we delve the more we recognise the mastery and stunning precision of the workings of a Higher Being, as was acknowledged by Bertrand Russell and even more recent counterparts.

We run the risk, however, of undermining those very principles and beliefs we have fought so hard to define and preserve. As we move in this age from the rational to the empirical, we must strive to ensure that these values and beliefs are not only transmitted but internalised so as to foster discovery of intrinsic worth, individual speciality and thereby the unending possibility of intellectual, mental, emotional and spiritual development.

There is need for the recognition and celebration of demonstrated competence and awareness of values within a system based – not on freedom as initially conceptualised by Plato, or equality as articulated by Marx and Ingles, but of a system based on justice – the most delicate of balances between the individual and society. The happy medium as described in the Qur’an.

And was it not Rumi who said “the middle path is the way to wisdom”?

This quest for balance led to the emergence of value systems – ethical codes or guidelines for daily life – some of which we recognise as religions.

Whether we believe they were revealed through divine intervention, as is upheld in Islam and Catholicism, or rather championed by visionaries or opportunists, as is maintained in more secular schools of thought, the fact remains these systems emerged at different times and in different civilisations around the globe.

All the while, indeed, sometimes seemingly in parallel, mankind has marched on, dreaming of perfection and the evolution of superman, as was considered by Dewey, Shaw and Nietzsche. Some see the development process as linear progression, while others advocate cyclic tendencies and act accordingly.

And yet here we are today – a diverse and yet dominant species who (as identified by Sayed Ashraf) have been able to mirror the characteristics of our Creator in our understanding of ourselves, our interaction with our fellow man and even the physical environment.

Yet still, the deeper we delve the more we recognise the mastery and stunning precision of the workings of a Higher Being, as was acknowledged by Bertrand Russell and even more recent counterparts.

We run the risk, however, of undermining those very principles and beliefs we have fought so hard to define and preserve. As we move in this age from the rational to the empirical, we must strive to ensure that these values and beliefs are not only transmitted but internalised so as to foster discovery of intrinsic worth, individual speciality and thereby the unending possibility of intellectual, mental, emotional and spiritual development.

There is need for the recognition and celebration of demonstrated competence and awareness of values within a system based – not on freedom as initially conceptualised by Plato, or equality as articulated by Marx and Ingles, but of a system based on justice – the most delicate of balances between the individual and society. The happy medium as described in the Qur’an.

And was it not Rumi who said “the middle path is the way to wisdom”?

Friday 21 September 2007

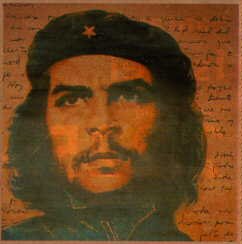

Pursuing Individual Freedom for Collective Progress

(The following is a speech delivered to an educational institution on the occasion of Emancipation in the Caribbean - a celebration of the end of slavery. Presentations by departments featured Freedom Fighters from various continents)

We have chosen to focus on the freedom fighter – and that is admirable in its recognition of the contribution of individuals to the progression of humankind. It is also serendipitous that I am asked, having been associated with the Centre for Leadership, wherein we can appreciate the challenges in influencing the behaviour – and in many instances the will of people – to effect change.

We have heard from the various centres on the struggles of people throughout the world, and whilst it suggests that trouble; problems and challenges that we may wrestle with are common to persons on the other end of the earth, it also gives hope that in every instance there were persons with the fortitude, the drive to see things the way they should be and then go to whatever means to realise their visions – even if it costs them their lives – even, in fact, their knowing that they may never live to see the results.

But the challenges they faced are as diverse as their approaches to resolve. It is in recognition of this fact that I focus on the changes in the forms of domination over the ages of man.

Firstly there was physical control – accentuated by firstly strategies to conquer and later on developments in weaponry. But the downtrodden outnumbered the privileged, and the control was not sustainable. Then the domination evolved into political control, and took root. But the migration throughout the globe to some version of a democratic model – 1 individual:1 vote - meant that again the vastly outnumbered privileged class could not sustain their power and control.

They found infinitely more success in their economic mechanisms, and the lower classes of society were suddenly caught in conflict between castigating the opportunists and aspiring to their luxuries. The opposition has been and still is growing – but has been unable to date to effectively curb the advances made through economic penetration.

The single visionary hope of the non-aligned movement has faltered, and bi and multilateral trade has been dominated by the forces in power. Ironically, the economic mechanism on the macro level was and is still being fuelled by the economics at the micro level – individual greed and the thirst that perpetuates corruption.

Today, the mechanism of domination has emerged seemingly based on people’s aspirations to comfort – and is wielded under the banner of culture and social conformity. Today, we are barraged through the media with foreign values that appeal to the 'Id' in us all.

And this barrage has broadened in scope as it has delved in depth.

It has accompanied the media interfaces of the technological applications that have meshed into the very fabric of our lives – making us slaves to its lure. It has become distilled to almost the subconscious, leading us on to arrive at those very conclusions that would perpetuate our submission.

And how can we resist? When values and norms are in question, and the real becomes the ideal, the only avenue open to us is the power of the idea. The idea of a new ideal – one that would elevate and sustain the lives of the common man. The idea of a balance between our individual rights and responsibilities to our fellow human beings. The idea of being the pivot in the ever-changing struggle for equity and equality. Essentially, the idea of justice.

This is how we endure. We can be robbed of our liberty and our justice. We can be butchered outright or in slow, spiralling cycles. But we can never be deprived of our thoughts. Ideas. The singular infection that can override the shackles of restriction and the imposed ceilings of compliance.

The real power is the power to think. The power to choose. And action will follow. Naturally.

We have chosen to focus on the freedom fighter – and that is admirable in its recognition of the contribution of individuals to the progression of humankind. It is also serendipitous that I am asked, having been associated with the Centre for Leadership, wherein we can appreciate the challenges in influencing the behaviour – and in many instances the will of people – to effect change.

We have heard from the various centres on the struggles of people throughout the world, and whilst it suggests that trouble; problems and challenges that we may wrestle with are common to persons on the other end of the earth, it also gives hope that in every instance there were persons with the fortitude, the drive to see things the way they should be and then go to whatever means to realise their visions – even if it costs them their lives – even, in fact, their knowing that they may never live to see the results.

But the challenges they faced are as diverse as their approaches to resolve. It is in recognition of this fact that I focus on the changes in the forms of domination over the ages of man.

Firstly there was physical control – accentuated by firstly strategies to conquer and later on developments in weaponry. But the downtrodden outnumbered the privileged, and the control was not sustainable. Then the domination evolved into political control, and took root. But the migration throughout the globe to some version of a democratic model – 1 individual:1 vote - meant that again the vastly outnumbered privileged class could not sustain their power and control.

They found infinitely more success in their economic mechanisms, and the lower classes of society were suddenly caught in conflict between castigating the opportunists and aspiring to their luxuries. The opposition has been and still is growing – but has been unable to date to effectively curb the advances made through economic penetration.

The single visionary hope of the non-aligned movement has faltered, and bi and multilateral trade has been dominated by the forces in power. Ironically, the economic mechanism on the macro level was and is still being fuelled by the economics at the micro level – individual greed and the thirst that perpetuates corruption.

Today, the mechanism of domination has emerged seemingly based on people’s aspirations to comfort – and is wielded under the banner of culture and social conformity. Today, we are barraged through the media with foreign values that appeal to the 'Id' in us all.

And this barrage has broadened in scope as it has delved in depth.

It has accompanied the media interfaces of the technological applications that have meshed into the very fabric of our lives – making us slaves to its lure. It has become distilled to almost the subconscious, leading us on to arrive at those very conclusions that would perpetuate our submission.

And how can we resist? When values and norms are in question, and the real becomes the ideal, the only avenue open to us is the power of the idea. The idea of a new ideal – one that would elevate and sustain the lives of the common man. The idea of a balance between our individual rights and responsibilities to our fellow human beings. The idea of being the pivot in the ever-changing struggle for equity and equality. Essentially, the idea of justice.

This is how we endure. We can be robbed of our liberty and our justice. We can be butchered outright or in slow, spiralling cycles. But we can never be deprived of our thoughts. Ideas. The singular infection that can override the shackles of restriction and the imposed ceilings of compliance.

The real power is the power to think. The power to choose. And action will follow. Naturally.

Tuesday 21 August 2007

Be Yourself

Be yourself; everyone else is already taken. - Oscar WildeIt's quite possibly the most commonly used phrase in the history of advice: Be yourself. But it's such a vague adage. What do they really mean when they tell you to be yourself? And is it really as easy as it sounds?

Find yourself. You can't be yourself if you don't know, understand, and accept yourself first.

Stop caring about how people perceive you. The fact is, it really doesn't matter. It's impossible to be yourself when you're caught up in wondering "Do they think I'm funny? Does he think I'm fat? Does she think I'm stupid?" To be yourself, you've got to let go of these concerns and just let your behavior flow, with only your consideration of others as a filter—not their consideration of you.

Be honest and open. What have you got to hide? You're an imperfect, growing, learning human being. If you feel ashamed or insecure about any aspect of yourself—and you feel you have to hide those parts of you, whether physically or emotionally—then you have to come to terms with that and learn to convert your so-called flaws into individualistic quirks.

Relax. Stop worrying about the worst that could happen, especially in social situations. So what if you fall flat on your face? Or get spinach stuck in your teeth? Learn to laugh at yourself both when it happens and afterwards. Turn it into a funny story that you can share with others. It lets them know that you're not perfect and makes you feel more at ease, too.

Develop and express your individuality. Whether it's your sense of style, or even your manner of speaking, if your preferred way of doing something strays from the mainstream, then be proud of it.

Have a Productive Day. Accept that some days you're the pigeon, and that some days, you're the statue. People might raise eyebrows and even make fun, but as long as you can shrug and say "Hey, that's just me" and leave it at that, people will ultimately respect you for it, and you'll respect yourself.

There's a difference between being yourself and being inappropriately unrestrained. You might have your opinions, dreams, and preferences, but that doesn't mean you have to disrespect others by forcing them to acknowledge your views.

If fads or trends strike your fancy, don't avoid them! Being yourself is all about reflecting who you are inside in what you do, and what you like is what you like, no matter how trendy it is (or not trendy, for that matter)!

As the famous song goes, "Life's not worth a damn until you can say, I am what I am" - when you can sincerely say it, you will know that you can be yourself.

Just because you don't care about how people perceive you doesn't mean you shouldn't be aware of it, especially in situations where being yourself might be misinterpreted. For example, you might enjoy being friendly and flirtatious, but in some cultures, that might be perceived as a sexual invitation, and you could get yourself in trouble.

Find yourself. You can't be yourself if you don't know, understand, and accept yourself first.

Stop caring about how people perceive you. The fact is, it really doesn't matter. It's impossible to be yourself when you're caught up in wondering "Do they think I'm funny? Does he think I'm fat? Does she think I'm stupid?" To be yourself, you've got to let go of these concerns and just let your behavior flow, with only your consideration of others as a filter—not their consideration of you.

Be honest and open. What have you got to hide? You're an imperfect, growing, learning human being. If you feel ashamed or insecure about any aspect of yourself—and you feel you have to hide those parts of you, whether physically or emotionally—then you have to come to terms with that and learn to convert your so-called flaws into individualistic quirks.

Relax. Stop worrying about the worst that could happen, especially in social situations. So what if you fall flat on your face? Or get spinach stuck in your teeth? Learn to laugh at yourself both when it happens and afterwards. Turn it into a funny story that you can share with others. It lets them know that you're not perfect and makes you feel more at ease, too.

Develop and express your individuality. Whether it's your sense of style, or even your manner of speaking, if your preferred way of doing something strays from the mainstream, then be proud of it.

Have a Productive Day. Accept that some days you're the pigeon, and that some days, you're the statue. People might raise eyebrows and even make fun, but as long as you can shrug and say "Hey, that's just me" and leave it at that, people will ultimately respect you for it, and you'll respect yourself.

There's a difference between being yourself and being inappropriately unrestrained. You might have your opinions, dreams, and preferences, but that doesn't mean you have to disrespect others by forcing them to acknowledge your views.

If fads or trends strike your fancy, don't avoid them! Being yourself is all about reflecting who you are inside in what you do, and what you like is what you like, no matter how trendy it is (or not trendy, for that matter)!

As the famous song goes, "Life's not worth a damn until you can say, I am what I am" - when you can sincerely say it, you will know that you can be yourself.

Just because you don't care about how people perceive you doesn't mean you shouldn't be aware of it, especially in situations where being yourself might be misinterpreted. For example, you might enjoy being friendly and flirtatious, but in some cultures, that might be perceived as a sexual invitation, and you could get yourself in trouble.

Find Yourself

Do not let other people influence who you are. Don't talk bad about people because other people do.

Be yourself and make sure no one Influences who you are. It will make finding yourself even harder since people are influencing who you THINK you are.

Forget about what everyone else thinks you should do. The biggest obstacle to finding yourself is feeling like you have to mould yourself to other people's expectations. While you might not want to disappoint the people close to you, remember that if they really care about you, they'll want you to be happy--and who finds happiness as a puppet? As long as you continue to exist to fulfill other people's ideas of who you should be, you'll never know who you want to be. Remember, "He who trims himself to suit everyone will soon whittle himself away." -Raymond Hull

Find solitude. Get away from the expectations, the conversations, the noise, the media, and the pressure. Take some time each day to go for a long walk and think. Plant yourself on a park bench with a notebook and write. Take a long, thoughtful road trip. Whatever you do, move away from anything that distracts you from contemplating your life and where you want it to go.

Ask yourself every question in the book, questions that are difficult, that dare to look at the big pictures, such as:

If I had all the resources in the world - if I didn't need to make money - what would I be doing with my day to day life and why? Perhaps you'd be painting, or writing, or farming, or exploring the Amazon rainforest. Don't hold back.

What do I want to look back on my life and say that I never regretted? Would you regret never having traveled abroad? Would you regret never having asked that person out, even if it meant risking rejection? Would you regret not spending enough time with your family when you could? This question can be particularly difficult for some people.

If you had to choose three words to describe the kind of person you'd love to be, what would those words be? Adventurous? Loving? Open? Honest? Hilarious? Optimistic? Realistic? Motivated? Resilient? Don't be afraid to pick up a thesaurus.

Write down your answers. Beyond your time alone, it's easy for these thoughts to slip to the back of your mind and be forgotten. If you have them written down, then every time you reflect, you can review your notes and take it a step further, instead of answering the same questions all over again.

Act upon your new-found self-knowledge. Pick up those watercolors. Write a short story. Plan a trip to Fiji. Have dinner with a family member. Start cracking jokes. Open up. Tell the truth.

Whatever it is that you've decided you want to be or do, start being and doing it now.

Be ready for dead ends. Finding yourself is a journey, not a destination. A lot of it is trial and error. That's the price you pay in return for the satisfaction you receive: More often than not, you hit a bump in the road, and sometimes you fall flat on your face. Be prepared to understand and accept that this is a part of the process, and commit to getting right back up and starting over. It's not going to be easy--it never has been for anybody - but if you learn to see that as a chance to prove how much you want to find yourself, then you'll find fulfillment and security in your pursuit.

When you are yourself, then everyone will respect you more and treat you kindly.

Be yourself and make sure no one Influences who you are. It will make finding yourself even harder since people are influencing who you THINK you are.

Forget about what everyone else thinks you should do. The biggest obstacle to finding yourself is feeling like you have to mould yourself to other people's expectations. While you might not want to disappoint the people close to you, remember that if they really care about you, they'll want you to be happy--and who finds happiness as a puppet? As long as you continue to exist to fulfill other people's ideas of who you should be, you'll never know who you want to be. Remember, "He who trims himself to suit everyone will soon whittle himself away." -Raymond Hull

Find solitude. Get away from the expectations, the conversations, the noise, the media, and the pressure. Take some time each day to go for a long walk and think. Plant yourself on a park bench with a notebook and write. Take a long, thoughtful road trip. Whatever you do, move away from anything that distracts you from contemplating your life and where you want it to go.

Ask yourself every question in the book, questions that are difficult, that dare to look at the big pictures, such as:

If I had all the resources in the world - if I didn't need to make money - what would I be doing with my day to day life and why? Perhaps you'd be painting, or writing, or farming, or exploring the Amazon rainforest. Don't hold back.

What do I want to look back on my life and say that I never regretted? Would you regret never having traveled abroad? Would you regret never having asked that person out, even if it meant risking rejection? Would you regret not spending enough time with your family when you could? This question can be particularly difficult for some people.

If you had to choose three words to describe the kind of person you'd love to be, what would those words be? Adventurous? Loving? Open? Honest? Hilarious? Optimistic? Realistic? Motivated? Resilient? Don't be afraid to pick up a thesaurus.

Write down your answers. Beyond your time alone, it's easy for these thoughts to slip to the back of your mind and be forgotten. If you have them written down, then every time you reflect, you can review your notes and take it a step further, instead of answering the same questions all over again.

Act upon your new-found self-knowledge. Pick up those watercolors. Write a short story. Plan a trip to Fiji. Have dinner with a family member. Start cracking jokes. Open up. Tell the truth.

Whatever it is that you've decided you want to be or do, start being and doing it now.

Be ready for dead ends. Finding yourself is a journey, not a destination. A lot of it is trial and error. That's the price you pay in return for the satisfaction you receive: More often than not, you hit a bump in the road, and sometimes you fall flat on your face. Be prepared to understand and accept that this is a part of the process, and commit to getting right back up and starting over. It's not going to be easy--it never has been for anybody - but if you learn to see that as a chance to prove how much you want to find yourself, then you'll find fulfillment and security in your pursuit.

When you are yourself, then everyone will respect you more and treat you kindly.

Thursday 9 August 2007

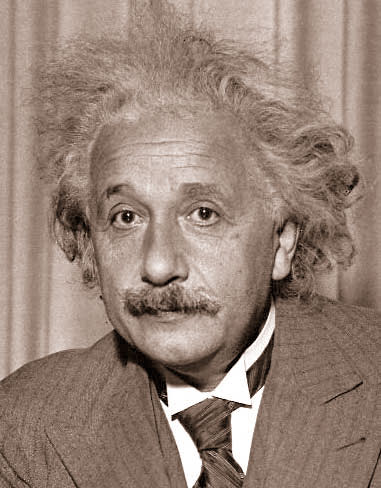

Bertrand Russell & Albert Einstein: Manifesto

Remember your humanity, and forget the rest.

Russell had begun the conference by stating:

"I am bringing the warning pronounced by the signatories to the notice of all the powerful Governments of the world in the earnest hope that they may agree to allow their citizens to survive."

In the tragic situation which confronts humanity, we feel that scientists should assemble in conference to appraise the perils that have arisen as a result of the development of weapons of mass destruction, and to discuss a resolution in the spirit of the appended draft.

We are speaking on this occasion, not as members of this or that nation, continent, or creed, but as human beings, members of the species Man, whose continued existence is in doubt. The world is full of conflicts; and, overshadowing all minor conflicts, the titanic struggle between Communism and anti-Communism.

Almost everybody who is politically conscious has strong feelings about one or more of these issues; but we want you, if you can, to set aside such feelings and consider yourselves only as members of a biological species which has had a remarkable history, and whose disappearance none of us can desire.

We shall try to say no single word which should appeal to one group rather than to another. All, equally, are in peril, and, if the peril is understood, there is hope that they may collectively avert it.

We have to learn to think in a new way. We have to learn to ask ourselves, not what steps can be taken to give military victory to whatever group we prefer, for there no longer are such steps; the question we have to ask ourselves is: what steps can be taken to prevent a military contest of which the issue must be disastrous to all parties?

The general public, and even many men in positions of authority, have not realized what would be involved in a war with nuclear bombs. The general public still thinks in terms of the obliteration of cities. It is understood that the new bombs are more powerful than the old, and that, while one A-bomb could obliterate Hiroshima, one H-bomb could obliterate the largest cities, such as London, New York, and Moscow.

No doubt in an H-bomb war great cities would be obliterated. But this is one of the minor disasters that would have to be faced. If everybody in London, New York, and Moscow were exterminated, the world might, in the course of a few centuries, recover from the blow. But we now know, especially since the Bikini test, that nuclear bombs can gradually spread destruction over a very much wider area than had been supposed.

It is stated on very good authority that a bomb can now be manufactured which will be 2,500 times as powerful as that which destroyed Hiroshima. Such a bomb, if exploded near the ground or under water, sends radio-active particles into the upper air. They sink gradually and reach the surface of the earth in the form of a deadly dust or rain. It was this dust which infected the Japanese fishermen and their catch of fish. No one knows how widely such lethal radio-active particles might be diffused, but the best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with H-bombs might possibly put an end to the human race. It is feared that if many H-bombs are used there will be universal death, sudden only for a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.

Many warnings have been uttered by eminent men of science and by authorities in military strategy. None of them will say that the worst results are certain. What they do say is that these results are possible, and no one can be sure that they will not be realized. We have not yet found that the views of experts on this question depend in any degree upon their politics or prejudices. They depend only, so far as our researches have revealed, upon the extent of the particular expert's knowledge. We have found that the men who know most are the most gloomy.

Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war? People will not face this alternative because it is so difficult to abolish war.

The abolition of war will demand distasteful limitations of national sovereignty. But what perhaps impedes understanding of the situation more than anything else is that the term "mankind" feels vague and abstract. People scarcely realize in imagination that the danger is to themselves and their children and their grandchildren, and not only to a dimly apprehended humanity. They can scarcely bring themselves to grasp that they, individually, and those whom they love are in imminent danger of perishing agonizingly. And so they hope that perhaps war may be allowed to continue provided modern weapons are prohibited.

This hope is illusory. Whatever agreements not to use H-bombs had been reached in time of peace, they would no longer be considered binding in time of war, and both sides would set to work to manufacture H-bombs as soon as war broke out, for, if one side manufactured the bombs and the other did not, the side that manufactured them would inevitably be victorious.

Although an agreement to renounce nuclear weapons as part of a general reduction of armaments would not afford an ultimate solution, it would serve certain important purposes. First, any agreement between East and West is to the good in so far as it tends to diminish tension. Second, the abolition of thermo-nuclear weapons, if each side believed that the other had carried it out sincerely, would lessen the fear of a sudden attack in the style of Pearl Harbour, which at present keeps both sides in a state of nervous apprehension. We should, therefore, welcome such an agreement though only as a first step.

Most of us are not neutral in feeling, but, as human beings, we have to remember that, if the issues between East and West are to be decided in any manner that can give any possible satisfaction to anybody, whether Communist or anti-Communist, whether Asian or European or American, whether White or Black, then these issues must not be decided by war. We should wish this to be understood, both in the East and in the West.

There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

Resolution:

We invite this Congress, and through it the scientists of the world and the general public, to subscribe to the following resolution:

"In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge publicly, that their purpose cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them."

Signed:

Max Born

Percy W. Bridgman

Albert Einstein

Leopold Infeld

Frederic Joliot-Curie

Herman J. Muller

Linus Pauling

Cecil F. Powell

Joseph Rotblat

Bertrand Russell

Hideki Yukawa

Russell had begun the conference by stating:

"I am bringing the warning pronounced by the signatories to the notice of all the powerful Governments of the world in the earnest hope that they may agree to allow their citizens to survive."

In the tragic situation which confronts humanity, we feel that scientists should assemble in conference to appraise the perils that have arisen as a result of the development of weapons of mass destruction, and to discuss a resolution in the spirit of the appended draft.

We are speaking on this occasion, not as members of this or that nation, continent, or creed, but as human beings, members of the species Man, whose continued existence is in doubt. The world is full of conflicts; and, overshadowing all minor conflicts, the titanic struggle between Communism and anti-Communism.

Almost everybody who is politically conscious has strong feelings about one or more of these issues; but we want you, if you can, to set aside such feelings and consider yourselves only as members of a biological species which has had a remarkable history, and whose disappearance none of us can desire.

We shall try to say no single word which should appeal to one group rather than to another. All, equally, are in peril, and, if the peril is understood, there is hope that they may collectively avert it.

We have to learn to think in a new way. We have to learn to ask ourselves, not what steps can be taken to give military victory to whatever group we prefer, for there no longer are such steps; the question we have to ask ourselves is: what steps can be taken to prevent a military contest of which the issue must be disastrous to all parties?

The general public, and even many men in positions of authority, have not realized what would be involved in a war with nuclear bombs. The general public still thinks in terms of the obliteration of cities. It is understood that the new bombs are more powerful than the old, and that, while one A-bomb could obliterate Hiroshima, one H-bomb could obliterate the largest cities, such as London, New York, and Moscow.

No doubt in an H-bomb war great cities would be obliterated. But this is one of the minor disasters that would have to be faced. If everybody in London, New York, and Moscow were exterminated, the world might, in the course of a few centuries, recover from the blow. But we now know, especially since the Bikini test, that nuclear bombs can gradually spread destruction over a very much wider area than had been supposed.

It is stated on very good authority that a bomb can now be manufactured which will be 2,500 times as powerful as that which destroyed Hiroshima. Such a bomb, if exploded near the ground or under water, sends radio-active particles into the upper air. They sink gradually and reach the surface of the earth in the form of a deadly dust or rain. It was this dust which infected the Japanese fishermen and their catch of fish. No one knows how widely such lethal radio-active particles might be diffused, but the best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with H-bombs might possibly put an end to the human race. It is feared that if many H-bombs are used there will be universal death, sudden only for a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.

Many warnings have been uttered by eminent men of science and by authorities in military strategy. None of them will say that the worst results are certain. What they do say is that these results are possible, and no one can be sure that they will not be realized. We have not yet found that the views of experts on this question depend in any degree upon their politics or prejudices. They depend only, so far as our researches have revealed, upon the extent of the particular expert's knowledge. We have found that the men who know most are the most gloomy.

Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war? People will not face this alternative because it is so difficult to abolish war.

The abolition of war will demand distasteful limitations of national sovereignty. But what perhaps impedes understanding of the situation more than anything else is that the term "mankind" feels vague and abstract. People scarcely realize in imagination that the danger is to themselves and their children and their grandchildren, and not only to a dimly apprehended humanity. They can scarcely bring themselves to grasp that they, individually, and those whom they love are in imminent danger of perishing agonizingly. And so they hope that perhaps war may be allowed to continue provided modern weapons are prohibited.

This hope is illusory. Whatever agreements not to use H-bombs had been reached in time of peace, they would no longer be considered binding in time of war, and both sides would set to work to manufacture H-bombs as soon as war broke out, for, if one side manufactured the bombs and the other did not, the side that manufactured them would inevitably be victorious.

Although an agreement to renounce nuclear weapons as part of a general reduction of armaments would not afford an ultimate solution, it would serve certain important purposes. First, any agreement between East and West is to the good in so far as it tends to diminish tension. Second, the abolition of thermo-nuclear weapons, if each side believed that the other had carried it out sincerely, would lessen the fear of a sudden attack in the style of Pearl Harbour, which at present keeps both sides in a state of nervous apprehension. We should, therefore, welcome such an agreement though only as a first step.

Most of us are not neutral in feeling, but, as human beings, we have to remember that, if the issues between East and West are to be decided in any manner that can give any possible satisfaction to anybody, whether Communist or anti-Communist, whether Asian or European or American, whether White or Black, then these issues must not be decided by war. We should wish this to be understood, both in the East and in the West.

There lies before us, if we choose, continual progress in happiness, knowledge, and wisdom. Shall we, instead, choose death, because we cannot forget our quarrels? We appeal as human beings to human beings: Remember your humanity, and forget the rest. If you can do so, the way lies open to a new Paradise; if you cannot, there lies before you the risk of universal death.

Resolution:

We invite this Congress, and through it the scientists of the world and the general public, to subscribe to the following resolution:

"In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge publicly, that their purpose cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them."

Signed:

Max Born

Percy W. Bridgman

Albert Einstein

Leopold Infeld

Frederic Joliot-Curie

Herman J. Muller

Linus Pauling

Cecil F. Powell

Joseph Rotblat

Bertrand Russell

Hideki Yukawa

Sunday 5 August 2007

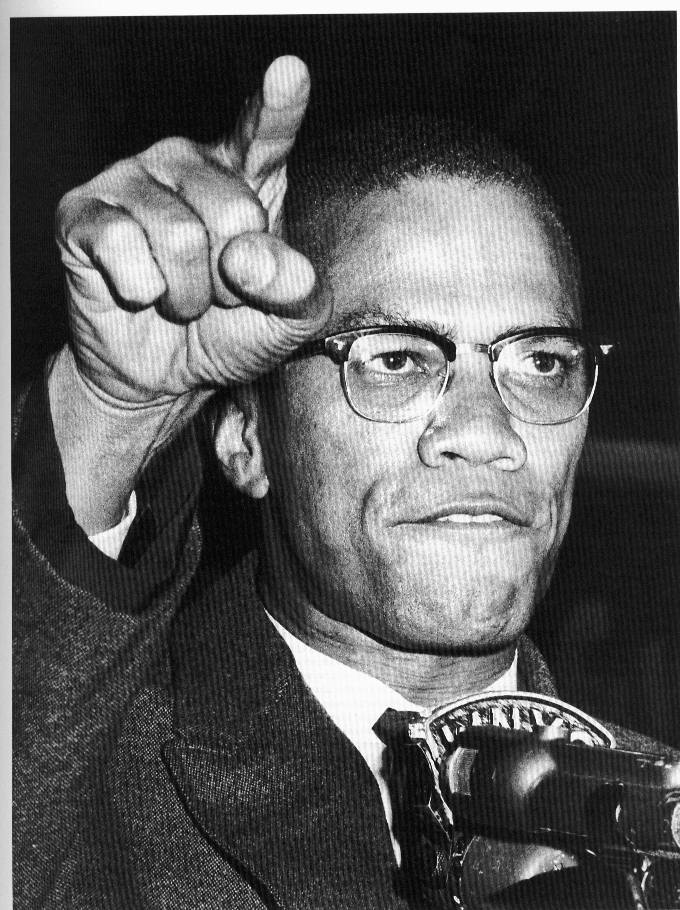

Malcom X: Letter from Hajj

Never have I witnessed such sincere hospitality and overwhelming spirit of true brotherhood as is practiced by people of all colors and races here in this Ancient Holy Land, the home of Abraham, Muhammad and all the other Prophets of the Holy Scriptures. For the past week, I have been utterly speechless and spellbound by the graciousness I see displayed all around me by people of all colors.

I have been blessed to visit the Holy City of Mecca. I have made my seven circuits around the Ka'ba, led by a young Mutawaf named Muhammad. I drank water from the well of the Zam Zam. I ran seven times back and forth between the hills of Mt. Al-Safa and Al-Marwah. I have prayed in the ancient city of Mina, and I have prayed on Mt. Arafat.

There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blonds to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and non-white.

America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. Throughout my travels in the Muslim world, I have met, talked to, and even eaten with people who in America would have been considered 'white'--but the 'white' attitude was removed from their minds by the religion of Islam. I have never before seen sincere and true brotherhood practiced by all colors together, irrespective of their color.

You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to re-arrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. This was not too difficult for me. Despite my firm convictions, I have always been a man who tries to face facts, and to accept the reality of life as new experience and new knowledge unfolds it. I have always kept an open mind, which is necessary to the flexibility that must go hand in hand with every form of intelligent search for truth.

During the past eleven days here in the Muslim world, I have eaten from the same plate, drunk from the same glass, and slept in the same bed (or on the same rug)--while praying to the same God--with fellow Muslims, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, whose hair was the blondest of blond, and whose skin was the whitest of white. And in the words and in the actions in the deeds of the 'white' Muslims, I felt the same sincerity that I felt among the black African Muslims of Nigeria, Sudan, and Ghana.

We were truly all the same (brothers)--because their belief in one God had removed the white from their minds, the white from their behavior, and the white from their attitude.

I could see from this, that perhaps if white Americans could accept the Oneness of God, then perhaps, too, they could accept in reality the Oneness of Man--and cease to measure, and hinder, and harm others in terms of their 'differences' in color.

With racism plaguing America like an incurable cancer, the so-called 'Christian' white American heart should be more receptive to a proven solution to such a destructive problem. Perhaps it could be in time to save America from imminent disaster--the same destruction brought upon Germany by racism that eventually destroyed the Germans themselves.

Each hour here in the Holy Land enables me to have greater spiritual insights into what is happening in America between black and white. The American Negro never can be blamed for his racial animosities--he is only reacting to four hundred years of the conscious racism of the American whites. But as racism leads America up the suicide path, I do believe, from the experiences that I have had with them, that the whites of the younger generation, in the colleges and universities, will see the handwriting on the walls and many of them will turn to the spiritual path of truth--the only way left to America to ward off the disaster that racism inevitably must lead to.

Never have I been so highly honored. Never have I been made to feel more humble and unworthy. Who would believe the blessings that have been heaped upon an American Negro? A few nights ago, a man who would be called in America a 'white' man, a United Nations diplomat, an ambassador, a companion of kings, gave me his hotel suite, his bed. ... Never would I have even thought of dreaming that I would ever be a recipient of such honors--honors that in America would be bestowed upon a King--not a Negro.

All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of all the Worlds.

Sincerely,

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz(Malcolm X)

I have been blessed to visit the Holy City of Mecca. I have made my seven circuits around the Ka'ba, led by a young Mutawaf named Muhammad. I drank water from the well of the Zam Zam. I ran seven times back and forth between the hills of Mt. Al-Safa and Al-Marwah. I have prayed in the ancient city of Mina, and I have prayed on Mt. Arafat.

There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blonds to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and non-white.

America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. Throughout my travels in the Muslim world, I have met, talked to, and even eaten with people who in America would have been considered 'white'--but the 'white' attitude was removed from their minds by the religion of Islam. I have never before seen sincere and true brotherhood practiced by all colors together, irrespective of their color.

You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to re-arrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. This was not too difficult for me. Despite my firm convictions, I have always been a man who tries to face facts, and to accept the reality of life as new experience and new knowledge unfolds it. I have always kept an open mind, which is necessary to the flexibility that must go hand in hand with every form of intelligent search for truth.

During the past eleven days here in the Muslim world, I have eaten from the same plate, drunk from the same glass, and slept in the same bed (or on the same rug)--while praying to the same God--with fellow Muslims, whose eyes were the bluest of blue, whose hair was the blondest of blond, and whose skin was the whitest of white. And in the words and in the actions in the deeds of the 'white' Muslims, I felt the same sincerity that I felt among the black African Muslims of Nigeria, Sudan, and Ghana.

We were truly all the same (brothers)--because their belief in one God had removed the white from their minds, the white from their behavior, and the white from their attitude.

I could see from this, that perhaps if white Americans could accept the Oneness of God, then perhaps, too, they could accept in reality the Oneness of Man--and cease to measure, and hinder, and harm others in terms of their 'differences' in color.

With racism plaguing America like an incurable cancer, the so-called 'Christian' white American heart should be more receptive to a proven solution to such a destructive problem. Perhaps it could be in time to save America from imminent disaster--the same destruction brought upon Germany by racism that eventually destroyed the Germans themselves.

Each hour here in the Holy Land enables me to have greater spiritual insights into what is happening in America between black and white. The American Negro never can be blamed for his racial animosities--he is only reacting to four hundred years of the conscious racism of the American whites. But as racism leads America up the suicide path, I do believe, from the experiences that I have had with them, that the whites of the younger generation, in the colleges and universities, will see the handwriting on the walls and many of them will turn to the spiritual path of truth--the only way left to America to ward off the disaster that racism inevitably must lead to.

Never have I been so highly honored. Never have I been made to feel more humble and unworthy. Who would believe the blessings that have been heaped upon an American Negro? A few nights ago, a man who would be called in America a 'white' man, a United Nations diplomat, an ambassador, a companion of kings, gave me his hotel suite, his bed. ... Never would I have even thought of dreaming that I would ever be a recipient of such honors--honors that in America would be bestowed upon a King--not a Negro.

All praise is due to Allah, the Lord of all the Worlds.

Sincerely,

El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz(Malcolm X)

MLK: I Have a Dream

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. [Applause]

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity.

But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition.

In a sense we have come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check -- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God's children. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?" We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day the state of Alabama, whose governor's lips are presently dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, will be transformed into a situation where little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith with which I return to the South. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with a new meaning, "My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee!

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! free at last! thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity.

But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize an appalling condition.

In a sense we have come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check -- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to open the doors of opportunity to all of God's children. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment and to underestimate the determination of the Negro. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?" We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive.

Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day the state of Alabama, whose governor's lips are presently dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, will be transformed into a situation where little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls and walk together as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.

This is our hope. This is the faith with which I return to the South. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with a new meaning, "My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous peaks of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee!

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! free at last! thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

Mandela: Rivonia Trial Opening Statements

I am the First Accused.

I hold a Bachelor's Degree in Arts and practised as an attorney in Johannesburg for a number of years in partnership with Oliver Tambo. I am a convicted prisoner serving five years for leaving the country without a permit and for inciting people to go on strike at the end of May 1961...

I have always regarded myself, in the first place, as an African patriot. After all, I was born in Umtata, forty-six years ago. My guardian was my cousin, who was the acting paramount chief of Tembuland, and I am related both to the present paramount chief of Tembuland, Sabata Dalindyebo, and to Kaizer Matanzima, the Chief Minister of the Transkei.

Today I am attracted by the idea of a classless society, an attraction which springs in part from Marxist reading and, in part, from my admiration of the structure and organization of early African societies in this country. The land, then the main means of production, belonged to the tribe. There were no rich or poor and there was no exploitation.

It is true, as I have already stated, that I have been influenced by Marxist thought. But this is also true of many of the leaders of the new independent States. Such widely different persons as Gandhi, Nehru, Nkrumah, and Nasser all acknowledge this fact. We all accept the need for some form of socialism to enable our people to catch up with the advanced countries of this world and to overcome their legacy of extreme poverty. But this does not mean we are Marxists.

Indeed, for my own part, I believe that it is open to debate whether the Communist Party has any specific role to play at this particular stage of our political struggle. The basic task at the present moment is the removal of race discrimination and the attainment of democratic rights on the basis of the Freedom Charter. In so far as that Party furthers this task, I welcome its assistance. I realize that it is one of the means by which people of all races can be drawn into our struggle.

From my reading of Marxist literature and from conversations with Marxists, I have gained the impression that communists regard the parliamentary system of the West as undemocratic and reactionary. But, on the contrary, I am an admirer of such a system.

The Magna Carta, the Petition of Rights, and the Bill of Rights are documents which are held in veneration by democrats throughout the world.

I have great respect for British political institutions, and for the country's system of justice. I regard the British Parliament as the most democratic institution in the world, and the independence and impartiality of its judiciary never fail to arouse my admiration.

The American Congress, that country's doctrine of separation of powers, as well as the independence of its judiciary, arouses in me similar sentiments.

I have been influenced in my thinking by both West and East. All this has led me to feel that in my search for a political formula, I should be absolutely impartial and objective. I should tie myself to no particular system of society other than of socialism. I must leave myself free to borrow the best from the West and from the East . . .

There are certain Exhibits which suggest that we received financial support from abroad, and I wish to deal with this question.

Our political struggle has always been financed from internal sources - from funds raised by our own people and by our own supporters. Whenever we had a special campaign or an important political case - for example, the Treason Trial - we received financial assistance from sympathetic individuals and organizations in the Western countries. We had never felt it necessary to go beyond these sources.

But when in 1961 the Umkhonto was formed, and a new phase of struggle introduced, we realized that these events would make a heavy call on our slender resources, and that the scale of our activities would be hampered by the lack of funds. One of my instructions, as I went abroad in January 1962, was to raise funds from the African states.

I must add that, whilst abroad, I had discussions with leaders of political movements in Africa and discovered that almost every single one of them, in areas which had still not attained independence, had received all forms of assistance from the socialist countries, as well as from the West, including that of financial support. I also discovered that some well-known African states, all of them non-communists, and even anti-communists, had received similar assistance.

On my return to the Republic, I made a strong recommendation to the ANC that we should not confine ourselves to Africa and the Western countries, but that we should also send a mission to the socialist countries to raise the funds which we so urgently needed.

I have been told that after I was convicted such a mission was sent, but I am not prepared to name any countries to which it went, nor am I at liberty to disclose the names of the organizations and countries which gave us support or promised to do so.

As I understand the State case, and in particular the evidence of 'Mr. X', the suggestion is that Umkhonto was the inspiration of the Communist Party which sought by playing upon imaginary grievances to enrol the African people into an army which ostensibly was to fight for African freedom, but in reality was fighting for a communist state. Nothing could be further from the truth. In fact the suggestion is preposterous. Umkhonto was formed by Africans to further their struggle for freedom in their own land. Communists and others supported the movement, and we only wish that more sections of the community would join us.

Our fight is against real, and not imaginary, hardships or, to use the language of the State Prosecutor, 'so-called hardships'. Basically, we fight against two features which are the hallmarks of African life in South Africa and which are entrenched by legislation which we seek to have repealed. These features are poverty and lack of human dignity, and we do not need communists or so-called 'agitators' to teach us about these things.

South Africa is the richest country in Africa, and could be one of the richest countries in the world. But it is a land of extremes and remarkable contrasts. The whites enjoy what may well be the highest standard of living in the world, whilst Africans live in poverty and misery. Forty per cent of the Africans live in hopelessly overcrowded and, in some cases, drought-stricken Reserves, where soil erosion and the overworking of the soil makes it impossible for them to live properly off the land. Thirty per cent are labourers, labour tenants, and squatters on white farms and work and live under conditions similar to those of the serfs of the Middle Ages. The other 30 per cent live in towns where they have developed economic and social habits which bring them closer in many respects to white standards. Yet most Africans, even in this group, are impoverished by low incomes and high cost of living.

The highest-paid and the most prosperous section of urban African life is in Johannesburg. Yet their actual position is desperate. The latest figures were given on 25 March 1964 by Mr. Carr, Manager of the Johannesburg Non-European Affairs Department. The poverty datum line for the average African family in Johannesburg (according to Mr. Carr's department) is R42.84 per month. He showed that the average monthly wage is R32.24 and that 46 per cent of all African families in Johannesburg do not earn enough to keep them going.

Poverty goes hand in hand with malnutrition and disease. The incidence of malnutrition and deficiency diseases is very high amongst Africans. Tuberculosis, pellagra, kwashiorkor, gastro-enteritis, and scurvy bring death and destruction of health. The incidence of infant mortality is one of the highest in the world. According to the Medical Officer of Health for Pretoria, tuberculosis kills forty people a day (almost all Africans), and in 1961 there were 58,491 new cases reported. These diseases not only destroy the vital organs of the body, but they result in retarded mental conditions and lack of initiative, and reduce powers of concentration. The secondary results of such conditions affect the whole community and the standard of work performed by African labourers.

The complaint of Africans, however, is not only that they are poor and the whites are rich, but that the laws which are made by the whites are designed to preserve this situation. There are two ways to break out of poverty. The first is by formal education, and the second is by the worker acquiring a greater skill at his work and thus higher wages. As far as Africans are concerned, both these avenues of advancement are deliberately curtailed by legislation.

The present Government has always sought to hamper Africans in their search for education. One of their early acts, after coming into power, was to stop subsidies for African school feeding. Many African children who attended schools depended on this supplement to their diet. This was a cruel act.

There is compulsory education for all white children at virtually no cost to their parents, be they rich or poor. Similar facilities are not provided for the African children, though there are some who receive such assistance. African children, however, generally have to pay more for their schooling than whites. According to figures quoted by the South African Institute of Race Relations in its 1963 journal, approximately 40 per cent of African children in the age group between seven to fourteen do not attend school. For those who do attend school, the standards are vastly different from those afforded to white children. In 1960-61 the per capita Government spending on African students at State-aided schools was estimated at R12.46. In the same years, the per capita spending on white children in the Cape Province (which are the only figures available to me) was R144.57. Although there are no figures available to me, it can be stated, without doubt, that the white children on whom R144.57 per head was being spent all came from wealthier homes than African children on whom R12.46 per head was being spent.

The quality of education is also different. According to the Bantu Educational Journal, only 5,660 African children in the whole of South Africa passed their Junior Certificate in 1962, and in that year only 362 passed matric. This is presumably consistent with the policy of Bantu education about which the present Prime Minister said, during the debate on the Bantu Education Bill in 1953:

"When I have control of Native education I will reform it so that Natives will be taught from childhood to realize that equality with Europeans is not for them . . . People who believe in equality are not desirable teachers for Natives. When my Department controls Native education it will know for what class of higher education a Native is fitted, and whether he will have a chance in life to use his knowledge."

The other main obstacle to the economic advancement of the African is the industrial colour-bar under which all the better jobs of industry are reserved for Whites only. Moreover, Africans who do obtain employment in the unskilled and semi-skilled occupations which are open to them are not allowed to form trade unions which have recognition under the Industrial Conciliation Act. This means that strikes of African workers are illegal, and that they are denied the right of collective bargaining which is permitted to the better-paid White workers. The discrimination in the policy of successive South African Governments towards African workers is demonstrated by the so-called 'civilized labour policy' under which sheltered, unskilled Government jobs are found for those white workers who cannot make the grade in industry, at wages which far exceed the earnings of the average African employee in industry.